Books, School and War 📚

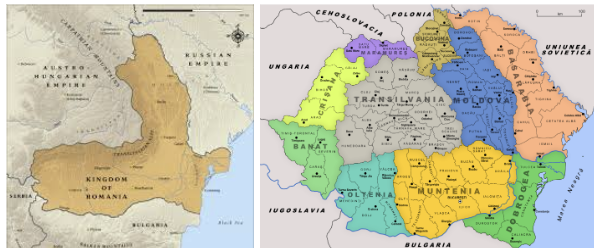

The basic facts of my great-grandfather's, Pârvu, life are simple: he was born in the 1880s (working back from his school years, I believe around 1885) into a relatively well-off, land-owning family in Arges County, Romania.

He studied at Scoala Normala (teacher training college), married a woman called Constanta (her story here). As was the custom, the wife moved to the husband’s village.

He fathered a daughter, Aurelia, my maternal grandmother, that was born after he was killed in World War 1 in 1917.

Two photos of him survive, his name in marble on a war monument, a few school notes and a few books. For all the tragically short life, he left, I think, a worthy legacy.

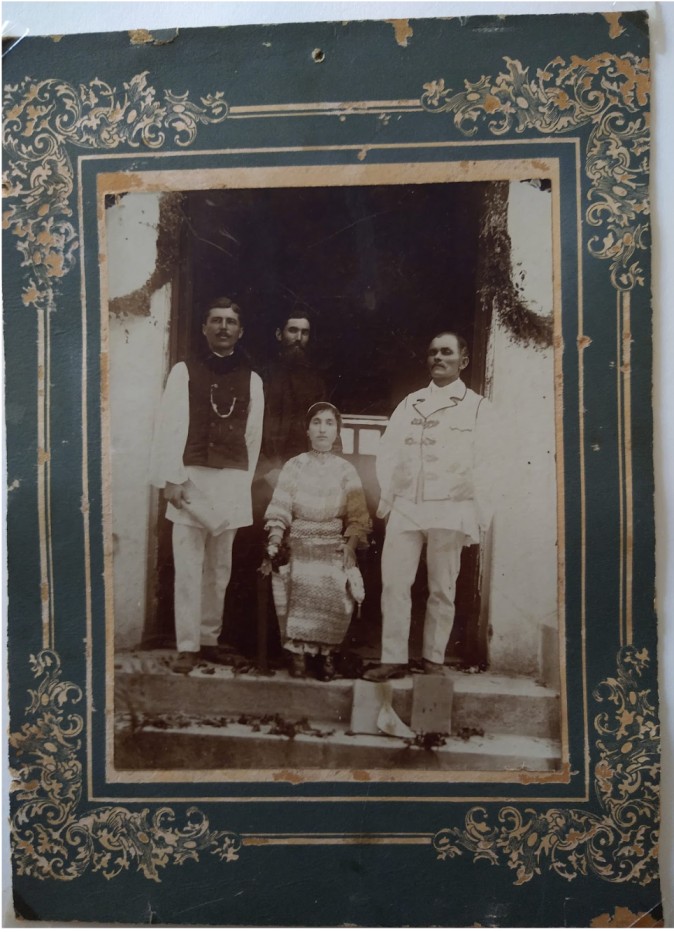

The photo

The other photo of Pârvu is more interesting. It shows him on the left and his wife, Constanta seated. The man on the right is his father. There is a family story about the occasion. While I could not confirm it from another source, I think there are elements on the photos that are consistent with the story.

The first world war

There are no specific details of his activity or letters during the war. All we have is his name and rank, a locotenent, at the top of this monument. The memorial is located in front of the school in his village and expresses the locals' gratitude.

Some generic WW1 facts (mainly from Wikipedia):

Romania was neutral for the first two years of WWI, entering on the side of the Allied Powers in August 1916. It had the most significant oil fields in Europe.

Romanian forces were involved in heavy battles on Oltul and Jiul valleys against advancing German forces. The Central Powers occupied Bucharest while the government and royal family moved to Iasi in Moldova, east Romania. The German offensive to conquer this last bit of Romania was stopped following several defensive victories in August 1917 at Mărăști, Mărășești, and Oituz, battles that took place under the slogan “Pe aici nu se trece”(They shall not pass - you will go no further). This is where Pârvu died.

The school

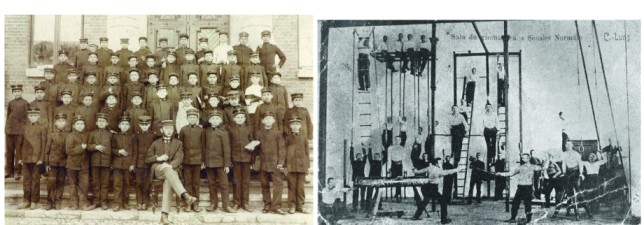

I am not sure what teacher training school Pârvu attended but I think that can only be one, really. The signatures of his colleagues (more on this later) indicate they came from different areas in the south of Romania, like Olt, Muscel and Dimbovita. I think I found the school most likely to be his alma mater, though I hope to be able to check one day.

According to this source the first teaching college also knows as Normal School in the south of the country was in a town called Campulung and set up in 1867 with the explicit purpose to train enough teachers to educate the population. Here is its selection policy:

The young man selected to become a teacher had to meet the following criteria: to be the son of a farmer born and raised in the countryside, to be no younger than 16 years old or older than 18 years old,

to be a graduate of four primary classes with an outstanding grade, to have full health …

The selected candidate had to bring a statement from the father by which he undertakes that his son will follow the school courses until graduation, and after graduation to stay at least six years at the post where he was assigned.

Admissions criteria sound very well thought out but they might have changed over time as far as ages are concerned, the pupils in the photo below look younger than 16. The school must have been boarding given the geographic spread of its students.

The books

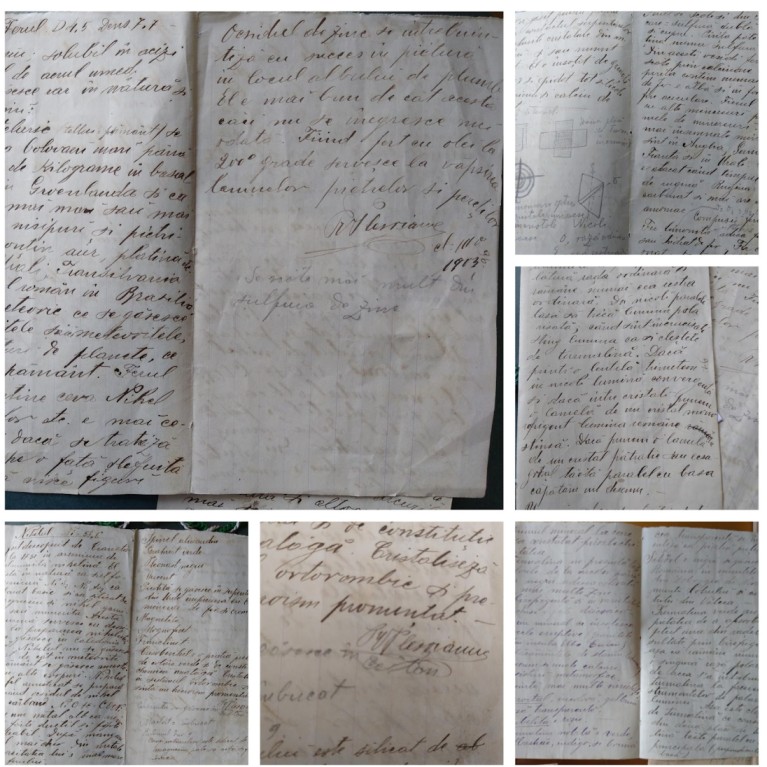

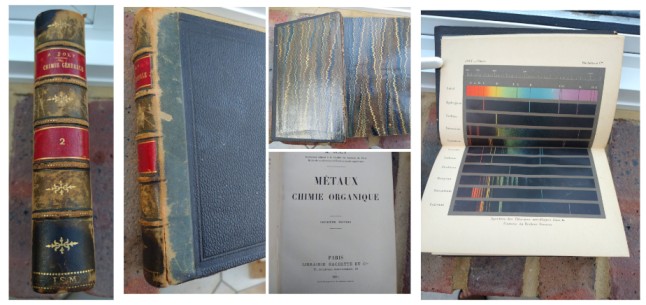

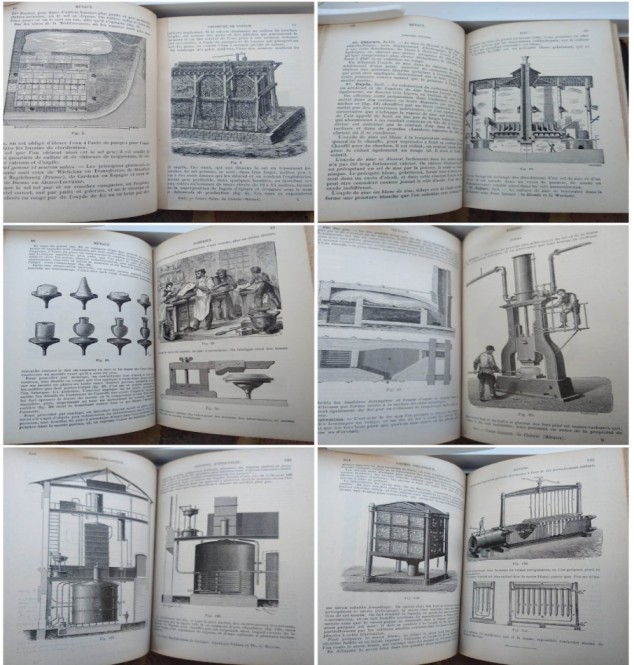

Chemistry

Back to more personal evidence. For a number of years, I had Pârvu’s chemistry notes. They describe common metals zinc, chrome, nickel and various combinations, carbonate this, sulphide that, their characteristics, the process of making mirrors and many more. I loved the beautiful calligraphy, the silky paper, his obvious dedication to his studies, his signatures and dates (including this one of his surname, from 1903, year III). I loved the fact that his only grandchild, my mother, later became a chemistry teacher.

My sons had the idea of searching for the periodic table to find out how many elements were known then. Much to our surprise, there was no periodic table at all! We looked it up and found 1869 as the year of Medeelev’s discovery but it looks like by 1896 it was not yet in the chemistry textbook of the leading French publishing house. The existence of this book makes me curious about different things. Why should he get a French chemistry book? It does feel too advanced. Was it because there were no Romanian books on chemistry at the time? Did he have a special interest in chemistry? How did he get the book? Did he order it somehow? A bookshop in Bucharest or Pitesti? Were French textbooks routinely stocked at the time? Unanswered questions.

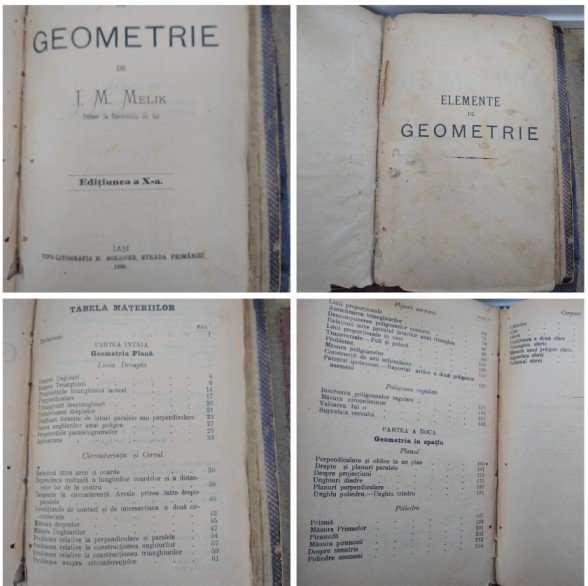

Geometry

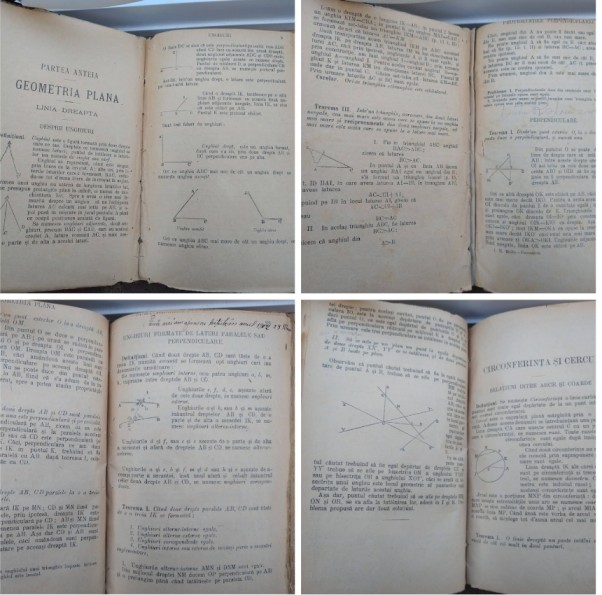

The other book of Pârvu I found is a geometry book. This has always been my favourite subject and I thought I “got it” from my math teacher dad. It seems there are geometry connections in my family.

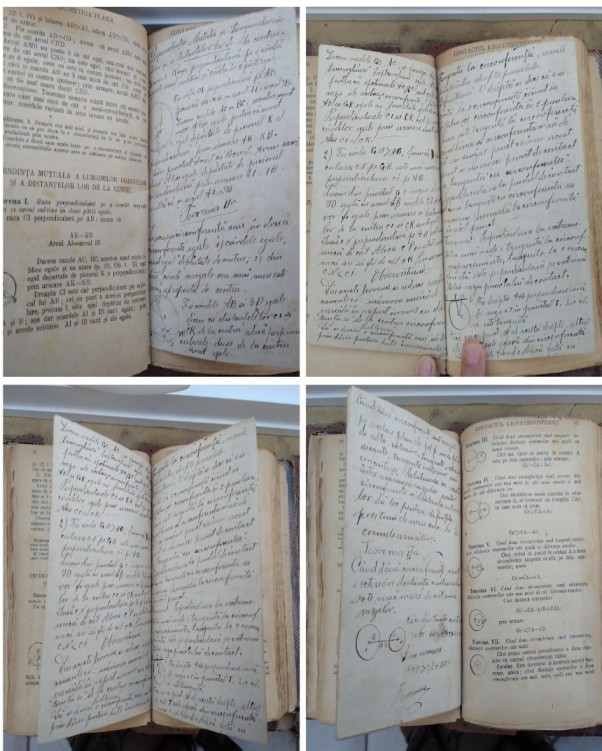

This is all together a very different book. It looks like home-bound, with frequent notes from Pârvu, like “We got till here by March 1903” or “Up till here in year II” and various comments, notes and annotations. From the notes, I believe the book was used for multiple school years. Some of his notes are bound into the book.

I think the French book must have been expensive so he kept it clean with notes on separate papers, while the geometry book is more of a cheaper workbook, annotated, signed on, scribbled on, way more personal.

The geometry book is in Romanian and is from 1899 (somehow the 10th edition at that time!).

Some familiar problems:

While the concepts have not changed for thousands of years, the language is very interesting. There are letters that no longer exist like e and i with a ˇ on top, plenty of archaic language, like crown for a vertex (in Romanian “crestetul unghiului”) and sole, like sole of the foot (“talpa”) for the base, excessively formal and latin words.

While the concepts have not changed for thousands of years, the language is very interesting. There are letters that no longer exist like e and i with a ˇ on top, plenty of archaic language, like crown for a vertex (in Romanian “crestetul unghiului”) and sole, like sole of the foot (“talpa”) for the base, excessively formal and latin words.

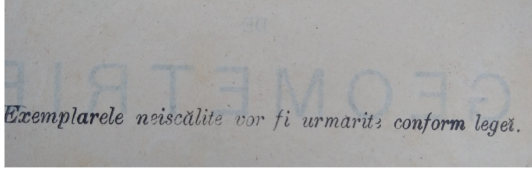

Some kind of legal(copyright?) notice “Unsigned copies will be pursued according to the law”:

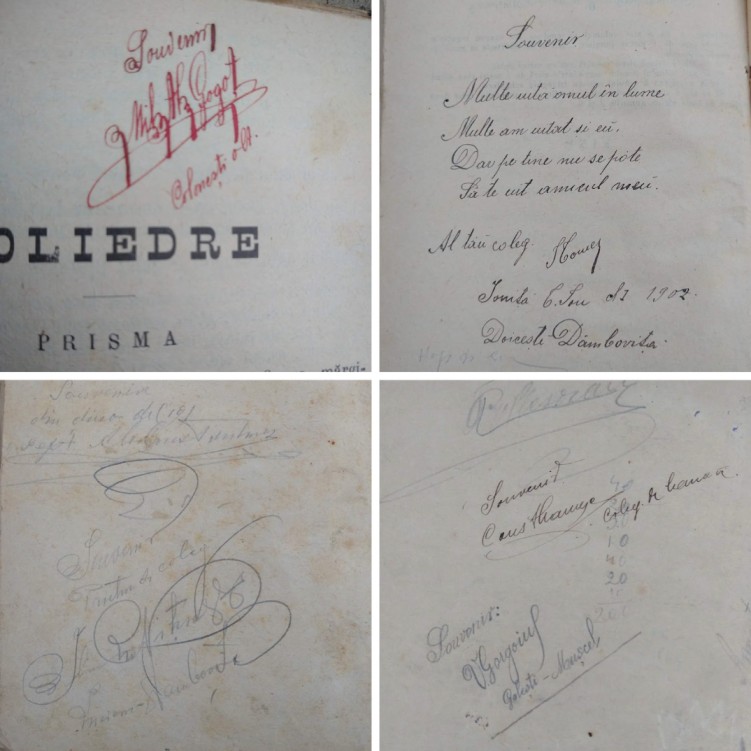

Probably the biggest surprise of the geometry book is that several of his colleagues signed the book usually with the title “Souvenir” and giving their names, sometimes the addresses too in the form of a village and county. A memorable dedication, a beautifully calligraphed little poem (even prettier handwriting than my great-grandfather!) from 1902 signed by a colleague, Ionita C Ion, says something like this (though a few commas wouldn’t have gone amiss):

Probably the biggest surprise of the geometry book is that several of his colleagues signed the book usually with the title “Souvenir” and giving their names, sometimes the addresses too in the form of a village and county. A memorable dedication, a beautifully calligraphed little poem (even prettier handwriting than my great-grandfather!) from 1902 signed by a colleague, Ionita C Ion, says something like this (though a few commas wouldn’t have gone amiss):

One forgets many things,

I forgot many things myself,

But one thing I won’t forget

It’s you, my friend

I hope you had a good life, Ionita C Ion.

Rest in peace, great-granddad!