Father

In the Romanian villages of yesteryear there were two positions that were held in highest respect and had a big social influence. Those were the priest and the primary school teacher in the village (often there was only one teacher). Various Romanian novels from XIX and XXth centuries have at least some story arcs, if not the main one, about aspirations and tribulations of poorer boys in their pursuit of one of these positions. It was a form of a social advancement, escaping the back breaking work of the land while still returning to the place of birth, usually to the delight of their parents, proud that their sons have climbed the social ladder. Unfortunately, it seems a little hard to imagine this respect today, especially for the teachers.

There were plenty of teachers in my extended family in the past but only one priest. He was called Florea (the male version of the name given to his sister, Floarea/Flora whose story is here - their parents must have really liked flowers!).

He was known as Father (in Romanian, taica popa) both in the family and in the wider community.

He was the younger brother of my great-grandmother, Constance (her story is here).

He cut an impressive figure. I met him as a child and I remember him as a tall man, still imposing, with a white beard and hair, kind blue eyes and a soft voice, but with an air of authority and deep knowledge, with everyone showing him great respect. He was about 80 at the time, obviously he looked to me as old as time, a lifetime of faith, suffering and wisdom etched on his face.

He had "it", whatever it might be: vocation, charisma, gift, calling, whatever it was.

For most of his life he was a priest in a village in the Arges county, both his and my great-grandmother Constance’s birth place, a place about 50 km away from the village where Constance lived after her marriage and with her daughter Aurelia.

Constance, young war widow as she was, visited her brother as often as she could to ask for advice and get moral and practical support. This continued throughout her life. When my grandmother, Aurelia came back to the countryside to stay with her mother during the years of second world war, she worked with her uncle on various social, cultural and educational charitable projects. A few photos from that time survive.

This one shows the Father seated with my grandmother and his niece, Aureliam standing behind the chair. I am intrigued by the empty chair. Did it mean anything? Someone absent? Was it meant to show a certain social or moral hierarchy in the way and order that the people are standing? Why didn’t Aurelia sit next to him? Was it considered disrespectful because of his position? But then why not take the chair away and have the other people just stand behind him? Family and society customs locked away in the little photo but no one left that can explain this. I have my theory that the empty chair represents Aurelia's father, WW1 hero( his story here) and it was a form of respect for his sacrifice but it's just my belief.

Another photo shows Father and Aurelia (on the right, a bit in the shade, wearing a traditional Romanian blouse, second tallest in the front row) at one charity event during World War 2 surrounded by village people.

Father had a very difficult time when the communists came into power given the combination of his family social and economical status and, of course, his faith and position. As described in sources such as this the doctrine of communist atheism took a hostile stance against religion. There were plenty of Orthodox priests and higher ranking church officials that collaborated with the communist authorities but Father was among the 5,000 Romanian Orthodox Christian priests that were imprisoned. In 1962–1964, the party leadership approved a mass amnesty, extended to, among other prisoners, approximately 6,700 “guilty” of political crimes.

One of my favourite things about Father was that in 1969 he somehow (I suspect he asked for some favours from fellow priests) came to Bucharest to perform, with the parish priest, the marriage ceremony for my parents.

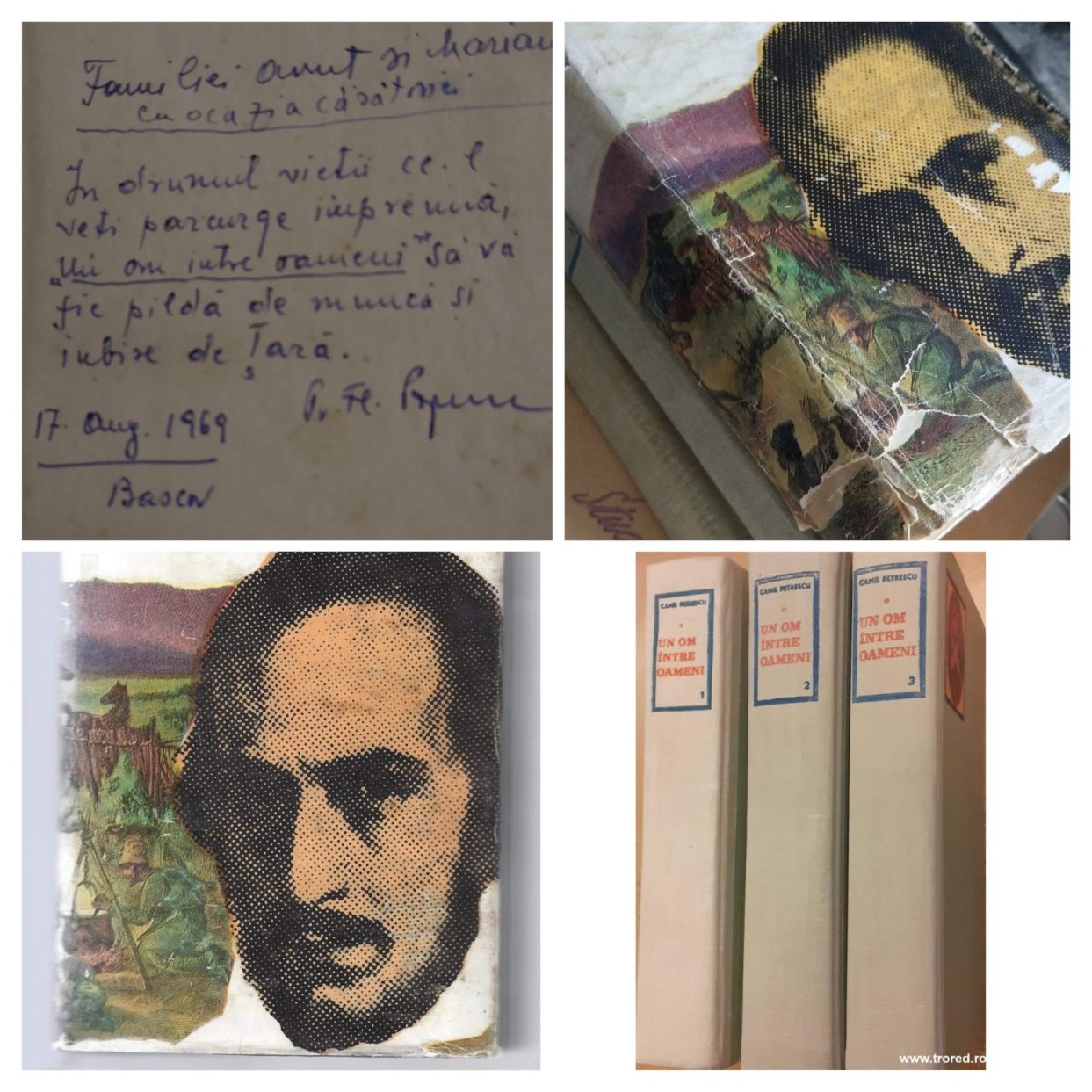

My parents got an unusual wedding gift from Father which I think it’s quite symbolic of the man he was. It’s a trilogy whose title I’d translate like “ A Man Among People” or “One Among Many”, book and title conveying, in my opinion, both belonging to a community and uniqueness. It is about a major Romanian historical figure, a revolutionary from 1848, Nicolae Balcescu, whose name is given to many Romanian institutions.

Balcescu was also on the highest denomination of the banknote at the time, 100 lei.

Father’s message to my newwly wed parents, on the inner cover of the book reads: “Throughout the life you’ll spend together,

let “One Among Many” be an example for you, of striving, work and love for the country”.

The date of the dedication is nearly a month after the wedding amd the location is his village so my parents must have visited him that summer, possibly during their honeymoon.

The book itself is quite heavy going, a vast (about 1800 pages) Balzac-like chronicle of the Romanian society in the XIX century. I don’t think my parents read it, at least not in its entirety. It wasn’t their sort of book. I read it when I was about 20. I found it interesting but I did not love it though I loved other works, more modern in style, by the same author, Camil Petrescu, who is a major Romanian novelist.

I love this Romanian custom of writing messages in books given as gifts.

Every time I pick the book I don't just have in my hand the story

of a Romanian hero

written by one of the best Romanian novelists, but, through this dedication, I feel I have in my hand the connection to all the generations that come before me, to Father’s, my great-grandmother's, grandmother's and my parents’ lives.

Father himself was “A Man Among People”.