The unexpected initial

I am not sure where the Romanian tradition of writing one’s full name to include the father's initial comes from. Maybe it has a Slavic origin? It was quite literally patriarchal. The official name would consist of last name, dad's initial then first and middle names. These days the initial might come from the person's middle name but, in this traditional model, it was the father's first name's initial.

As an example, all my school records had in the middle of my name the letter A from my dad's first name, Alexandru. Even my first passport had my dad's A between my last and first names(though not the later passports, the custom appeared to have been abandoned). Possibly some EU regulation? When I was 23 I took my first trip westwards with that first passport. I traveled by train from Bucharest and arrived the next morning at 8 am to Vienna. After a long day of sightseeing, I took the next night train to Italy. Sometimes during the night, a border police patrol got on the train and started to check the passengers’ passports. When it was my turn, the young Italian policeman started to ask me the usual border control questions that got a bit flirty until he asked me what the A in my passport stands for. “Alexandru”, I mentioned proudly. “Alessandro? You mean Alessandra?”, “No, the male version”. He looked really confused as I was claiming the male name and swiftly returned me the passport without further discussion. I didn’t realise then that this was a cultural difference and that the initial could cause identity confusion.

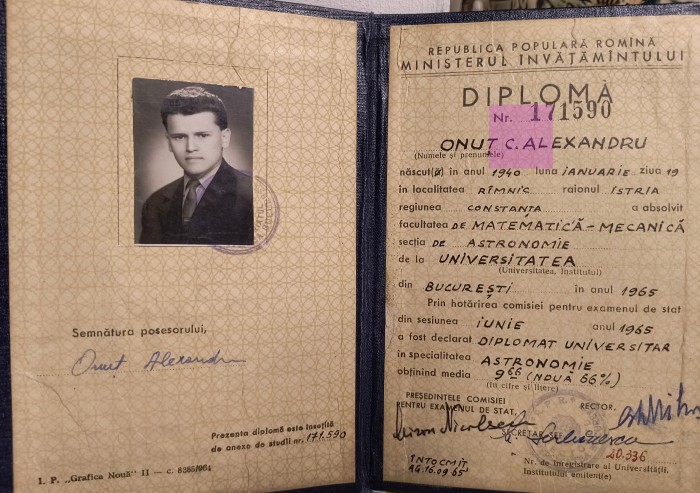

I recently came across an old school record, dad's university graduation diploma, that contains as father’s initial C, rather than the real one, I from Ion, my paternal grandad's name, and an old, and altogether darker, story came back to me.

I wrote here about my paternal grandfather, Ion: how he was sent to labor camp when the communists came to power, how the family moved to Bucharest from their village close to the Black Sea and how, in the late 70s, the political prisoner status of his father threatened to curtail the career advancement of one of my uncles.

The communist political system in Romania, from 1945 till 1989, was not the same during this whole period. The early, Stalinist years from after WW2 to early 60s were the worst, particularly the 50s, (they are sometimes known as the obsessive decade), the height of the communist abuses. Then there was some relative liberalisation (roughly mid ‘60s to mid to late ‘70s), before things got bad again in the 80s.

This is the story of how my dad’s family lived through that difficult 50s decade and how that puzzling initial came to be in a way that could only have happened during that time in our history. With my grandad at the labor camp and the land confiscated, it became clear that there was no future in the countryside, particularly for the three young sons and that the family would need to try their luck in Bucharest.

The first to move were my dad with his elder brother in 1954, when they were 14 and 24 respectively. My dad was, by a mile, the most academically gifted of his family.

He still had some catching up to do after his village education but, after an entry exam, he

got in to a very good high school in Bucharest, "Ion Neculce".

Meanwhile, his brother, Nelu, got a job, looked after my dad, found a place to stay, connected to other extended family and neighbours that were doing the same move to the capital and, in general, prepared the move to Bucharest for the rest of the family.

How he achieved all of these, I never asked and he never spoke about it.

At that time in the ‘50s, children of political prisoners could not go to university, which meant my dad could not continue to study after he graduated from high school. A solution was found, though. Though he had two living, loving parents, my dad was adopted by someone with a clean record. That someone was his uncle, my grandfather’s brother, Constantin. That's were the C, on my dad's graduation diploma comes from, it was really his uncle initial. Later on, I saw my mother tearing apart and chucking away a document dissolving this adoption. It would have been handy to establish a timeline and maybe answer some questions as how he got away with this: was the name of the father at birth not mentioned, any reason for the adoption given? Surely my dad had to be a minor to be adopted, so the adoption must have happened the latest in 1957. Even after the adoption, my dad did not go straight to university. Was it to avoid attention to this subterfuge because the ink was still wet on the adoption paper, or for money reasons or something else?

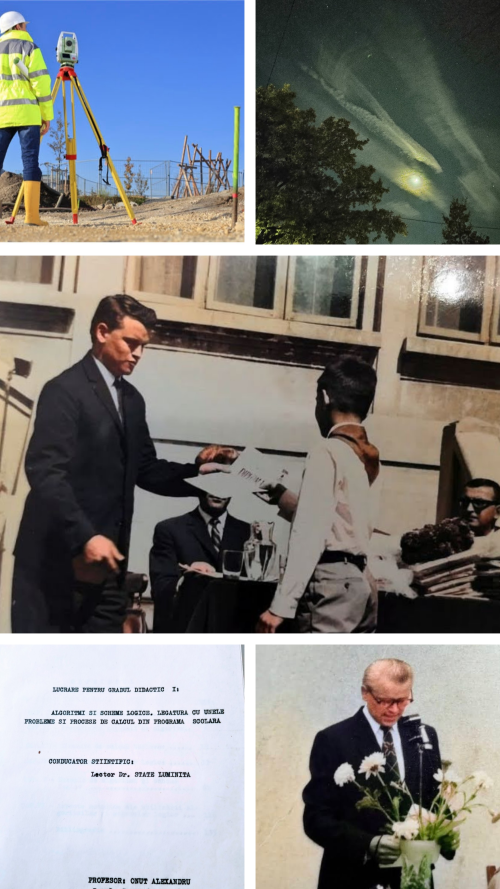

As a 18 year old, my dad trained and then worked as a cadastral officer, a profession in the field of land surveying, measuring distances and heights.

It suited him well, with his math skills and whenever I pass one these days, I imagine dad using similar triangles to compute the lengths and heights of buildings all these years ago.

It seems strange that he needed an adoption to get to uni but equally strange that being adopted by his uncle was enough to fool the system. This was pre-computers era so maybe it was not easy to cross check documents? At least it was his paternal uncle that adopted him, so my dad got to keep his last name. It is only this quirky father’s initials in the school record, C, instead of his dad’s I, that show how the “sins” of the fathers affected the sons during that time. This adoption was hardly ever mentioned in my childhood. Strictly speaking, it was a sham adoption and you wouldn't want to advertise that you fooled the communist restrictions this way.

While a student, my dad tutored his older brothers who had much worse schooling than him, as well as being far less academic. With his help, the brothers also got admitted to uni as mature students on some less demanding programs and eventually graduated with economics degrees. Both my uncles had really good careers, achieving high managerial positions in two state companies(the only kind for most of their working lives) and this wouldn’t have been possible at that time without a degree.

Maybe I got a bit brainwashed by the reality TV's talk of "the journey", or the growth mindset, or that countryside has different connotations where I live, in the UK. For me it's precisely their humble beginnings and the huge difficulties that they faced that makes what they achieved, from survival to the upward social mobility, more impressive.

Still, the fact that this bogus adoption was necessary is a testament of those difficult times that I hope will never come back. A lot is hidden behind that innocuous initial.