Brave Swearing

I remember my paternal grandfather, Ion, also known as Nițǎ to the family, as a quiet and kind man.

He had a simple and unwavering Christian faith (“there is a big, almighty power above us all”, I can still hear him saying).

He was one the most long-lived of my family, pushing 90 when he died.

I was told that his family originated from Transylvania, Alba county, back in the days before WW1 when it was part of Austro Hungarian empire.

At some moment, in the early part of the 20th century, the family moved, or, even, was forced to move, to a different part of Romania, a village in Dobrogea, Constanta county, by the Black Sea.

I saw a birth certificate of my grandfather listing a village in Constanta county as his birth place in 1906 though the certificate itself was written in 1950, so who knows.

Anyway, he was the eldest son( birth order is quite significant in traditional Romanian society), and took seriously the responsibility of looking after his siblings (a brother and two sisters that I met).

He had only four years of schooling. I remember hearing this from grown ups when I was in year 4 myself and I could not understand the dismissive tone: four years of school is quite advanced, isn't it?

During the first part of his life, for about 45 years, Ion worked the land with and for his family.

How did they get the first land in Dobrogea? Did they buy it with money they brought from Transylvania or was the reason they moved to Dobrogea some sort of land deal?

I don’t know how, but eventually the family acquired a fair bit of land over the years.

They poured all their resources into buying more and more land, and had at least 10 hectares or 24 acres (this was the maximum that could be recovered in the 1990s but I remember hearing from relatives

that they used to own a lot more).

In the late 1920s, Ion married a woman called Maria and they had three sons, with my father being his youngest.

I know they employed other villagers to work their land, but the family always did the back breaking work themselves too.

The memory of that exhaustingwork stayed with them for decades and they would still recall it in my childhood.

Their house was a modest adobe or mudbrick dwelling(sun-dried earth and straw), the remains of which I saw once in my childhood.

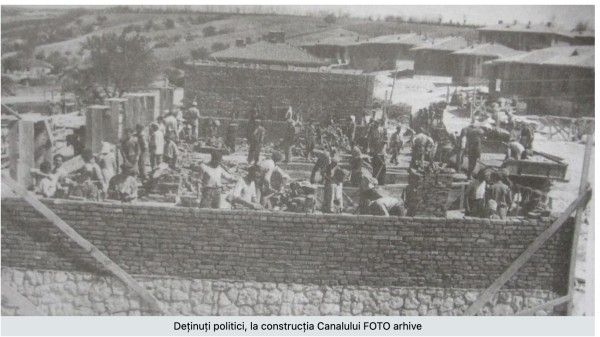

When the communists came into power, property, including land, was a theft. Not only was the land confiscated, but Ion was sent to a labor camp, the Danube to Black Sea canal and labeled enemy of the people. From this source, a British historian estimates that one million Romanians had been imprisoned in various prisons and labor camps, including those on the path of the canal.

Thankfully, Ion survived his years at the canal. I wish I had asked him more questions about his time there.

From 1954, the family started to move to Bucharest. First Ion’s eldest and youngest sons, aged 24 and 14 at the time, moved first. After a while, the rest of the extended family followed.

Ion did a few menial jobs in Bucharest for as long as he could, before retiring, with hardly any pension. He struggled financially in his old age and needed help from his sons to get by. While uneducated himself, he had a great respect for education as a way of making a better life (“ai carte, ai parte” he’d say or "knowledge is power").

He encouraged his sons to do it, which they did, though in a slightly unusual way (that’s a story for some other time).

Unlike other people that were sent to communist labor camps, he wasn’t starry eyed about the pre-communist times. When the liberals and peasant parties were reinstated in 1990, he thought they were all hustlers and crooks.

Sometime in the late ‘70s, Ion’s middle son, my uncle George, by then an accountant for the Romanian petroleum company, had the opportunity to work abroad, in an Arab country.

Romania had expertise in the extraction and processing of crude oil and deals were

struck with at least a few countries, Algeria and Libya were those my uncle eventually went to.

This was incredibly exciting and very lucrative for him!

But George had a black mark on his file because of his father's “an enemy of the people” status.

Somehow, George convinced his bosses to give him a chance, but the party officials wanted to first see if the enemy, Ion, had learned the lessons from his punishment.

At that time, the slightest political joke or protest could land you in prison.

My uncle later told me how the meeting went. He had pleaded: “Daddy(he really called him like that, even as a grown man), you must tell them that you understand the communists are right and you repent for what you did. Please, daddy, it’s really important! Just say it once, it doesn’t matter”. Ion nodded his agreement.

Two party officials (I think it’s fair to say, these were not the top brass but more likely the bottom of the pile) came to my grandfather's modest two rooms. Ion was seated on his bench, the two officials on the chairs and George nervously standing.

“So, comrade Onuț” started one of the officials, “do you now see the errors of your ways? Do you understand why communists are good and how they think of sending your son abroad. Do you understand this now?”. My grandfather took a while to respond.

“Communists, yes. F.ck them up their ars..!” he answered angrily. Three jaws hit the floor at the same moment with George needing to sit at this point.

“What did they have with my horses to shoot them, f.ck all the communist criminals?” This referred to a shameful act at the beginning of the communism in the Romanian villages when half of the millions of horses were shot. The Soviets brought, or were supposed to bring, tractors to work the land and, by this twisted logic, the horses were no longer needed, so they should be shot.

“They took my animals and brought them to the collective farm and they left them to die of hunger, those f.ckers! Florica, she kept my three sons alive during the war with her milk and they took her and left her to die of hunger and thirst! What has Florica done to you?! Was she a traitor, conspiring against the regime?!” continued Ion angrily, referring to his best cow. Animals were often confiscated with little thought and, it sounds like, in this case, they were brought somewhere but not given any feed or water so they died suffering. I have no idea how representative this case was.

For about 10 minutes, according to George, Ion carried on swearing at the communists and ranting about the horses, Florica and all the other animals.

Curiously, there was no mention of his years at the canal, just the crimes against his animals.

Somehow, the officials left (I am sure the goodbyes were a bit awkward) and George said he didn’t have the heart to reproach his dad this outburst.

For all the injustices that he suffered, I am glad my grandfather survived the hard labor and the system that introduced it and that he got his chance to tell to some representatives of the system what he thought of them in this salty way. It must have felt so good to unleash the anger and suffering accumulated over decades.

Speak truth to power! And swear to its face if you dare!